Two Things at Once

It’s important to be able to hold two ideas in your head at the same time, even if those two ideas might compete or conflict with one another. Even if they might cause discomfort. Here are my two ideas today:

First, we have to be able to work on our problems through spirited debate and not through coercion or violence. There’s no guarantee that we’ll reach a resolution and there’s certainly no guarantee that, if we manage to, it’ll be a resolution that we want. We might lose the argument; we might not have the necessary votes; or we might have to compromise for the time being. That feels miserable, especially when we feel like the stakes are so high and when losing the argument or the vote might mean that someone suffers.

Second, the people with whom we are arguing about current policies or the future of this country are people with whom we have deep disagreements, who might believe and say terrible things about us or the people we care about, and—worst of all—who might not be (or might seem not to be) committed to the same broad communal project that we are. I cannot and will not celebrate attempts to silence them, even if they absolutely would celebrate attempts to silence me.

I’m fully committed to both of these things and I’ll be honest that it’s incredibly difficult to hold onto that commitment on a daily basis. I’ve spent a lot of time lately sitting with the discomfort of believing both of these things deeply.

Charlie Kirk’s murder hit me much harder than I ever could have anticipated, not because I liked or agreed with him but because I disliked and disagreed with him so vehemently. To put a finer point on it, I feel as though I had a personal relationship with Kirk over the past decade, one that consisted of him making my life worse.

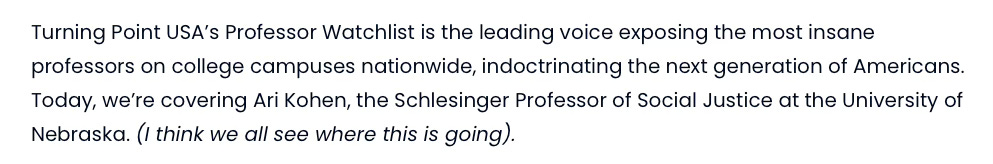

Kirk built an organization (Turning Point USA) and a series of interconnected websites (Campus Reform, Professor Watchlist) that were explicitly designed to erode Americans’ trust in education (especially higher education), to question the whole concept of expertise, and to launch a McCarthy-esque campaign against individual university professors. And then he and his allies dressed the whole thing up in the language of the Constitution and sold it to credulous journalists, high school teachers, students, and the public at large as young conservatives who were free speech advocates. They claimed that they love to debate ideas, that they wanted everyone to feel free to say whatever they wanted, and they loved watching Charlie destroy the libs. And yet, when someone called them a mean name, they cried and demanded punishments be meted out on the “intolerant Left.”

Of course, their aims were very clear at the time to anyone who wanted to pay attention, and they were certainly well understood by the billionaires who backed Kirk and by right-wing media personalities like Tucker Carlson who amplified these messages to tens of millions of people on television. And their supposed love of free speech certainly didn’t extend to the professors who ended up on their Watchlist website for the “crime” of holding political opinions that Kirk and his allies didn’t like. Kirk and the large following he built spent years hounding me and many of my colleagues at universities around the country. Thousands of calls and emails came in demanding that faculty members be fired or disciplined, instructors lost their jobs, and inboxes were flooded with hate mail and threats.

All of this information has seemingly vanished from public view in the overwhelming rush to memorialize Kirk as a champion of free speech and open debate, liberal values that simply were not present in the political activism that made him famous and launched him into the conservative stratosphere in the mid-2010s. In the time since Kirk’s murder, I’ve found myself explaining Turning Point USA and the Professor Watchlist to dozens of well-meaning people who have told me that they disagreed with Kirk’s politics but really respected his commitment to free speech. They’ve been legitimately shocked to learn that Kirk’s organization was designed to target not only my colleagues but also me, that their explicit goal was for professors to be punished for their political opinions. To me, and I suspect to most of my colleagues, Turning Point’s illiberal attacks on political speech opinions will be Kirk’s central legacy. And it’s thus no major surprise that people are being silenced—including by the government—if they speak out in ways that challenge the narrative of Kirk as free speech martyr.

We need to be able to hold two ideas in our heads at the same time even, or especially, when they cause discomfort. Kirk was a beloved activist to many people who agreed with him and he was a powerful and dangerous bully to those who didn’t. He said things that were designed to cause real harm to people—often people who were already marginalized in our society—and he also had a right to (and we as a society had an obligation to ensure that he could) say those things without fear of violence. He believed in free speech as long as he was the one speaking and he—and many of his allies—find it obvious that the same freedom shouldn’t extend to those with whom they disagree. It’s uncomfortable to recognize that all of these things can be true at the same time. As liberals, it’s profoundly important to sit with the discomfort so that we don’t ignore the part of each of those statements that doesn’t align with our own political worldview.

Thank you for sharing this.

I see you were added to that watchlist for your stance that people who do the "ok" hand gesture are white nationalists and that white nationalism is on the ballot. I am curious what your current position is on this.